Puente La Reina de Jaca

The mill got its water from the Río Aragón Subordán.

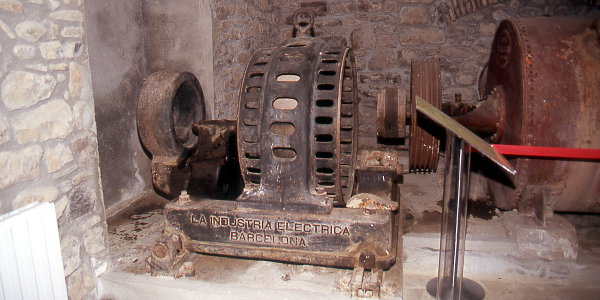

The building has undergone major improvement works and used as an office building since 2009. The original volume was preserved but the walls, though that was custom, were not whitewashed again. The museum takes only a fraction of the space on level -1 where two turbines and a dismantled generator are on display.

The original text with my translation follows together with some comments.

Pablo Martínez Hermida, vecino de Puente la Reina de Jaca, es una de las pocas personas que recuerda los detalles de una infraestructura que fue de gran importancia no sólo para la localidad, sino para gran parte de la Canal de Berdún, el Molino de Astorito o Azorito, villa medieval que dio origen a la actual Puente la Reina.

Pablo, que junto con su familia son los actuales panaderos de la localidad (Panadería Apiquera), nació en 1926 y según cuenta, el molino ya existía. Su orígen se desconoce, aunque se sabe que en el siglo XVIII, y ya con la villa de Astorito desaparecida, éste era el único inmueble que quedaba como recuerdo del poblado medieval. Un edificio que ha llegado hasta nuestros días, aunque sus funciones ya no son industriales sino administrativas, es la Sede de la Comarca de La Jacetania en Puente la Reina.

Pablo recuerda que el molino, era como el centro social de Puente la Reina y gran parte de la Canal. Entonces, en los pueblos había hornos comunales, las mujeres preparaban la masa en casa y los cocían en los hornos; pero para ello era necesario tener el trigo molido y todas las familias pasaban por el molino e intercambiaban noticias e informaciones. El actual panadero indica que la instalación contaba con dos muelas: Una era para el trigo, la otra para cebada. Un alimento, este último, que se empleaba, para la crianza de los cerdos, principalmente, comenta Pablo Martínez.

El uso del molino para la producción harinera fue la primordial. Casi todo el año era empleado para transformar el trigo y hacer pan. Algo que según recuerda Pablo generaba cierta saturación: Al día se podían moler unos 1.000 kilos, pero cada saco (de entre 5 y 10 kilos) tardaba unas 3 horas, así que había días en que buena parte de la jornada teníamos que estar allí esperando, señala. Además Pablo comenta que, como era un molino privado había que pagar por su uso. Sobre las tarifas, el actual panadero no las recuerda, si bien apunta que se fijaban en función de la cantidad total que se molía.

Pablo indica que en los años 20, aprovechando que la canal - recientemente recuperada y rehabilitada- estaba en altura, respecto al molino, éste añadió a sus funciones una nueva: Empezó a generar electricidad, recuerda. Pablo explica que la canal venía del Aragón Subordán, porque aunque no se sabe exactamente donde estaba el pueblo de Astorito, unas excavaciones que se hicieron a principios de los 90 localizó un cementerio, que se supone que era del poblado, y su ubicación estaba en esa dirección, entre la actual carretera a Pamplona y la de Hecho.

Así, el molino se convirtió en, la central de toda la Canal de Berdún, apunta Pablo Martínez. Suministraba luz a casi toda la Canal, Bailo, Larués, Santa Engracia, ... Aunque aquella luz no se podía comparar con la de ahora, una bombilla apenas alumbraba, pero algo era. Esta función de central hidroeléctrica acompañó a la de molino harinero hasta la década de los 50. El último propietario fue un catalán llamado Ramón Trullas que ha mediados del siglo pasado, con toda la familia, dejó Puente la Reina y el molino se quedó como bien comunal del pueblo.

Hasta la actualidad este edificio ha tenido diversas funciones, las más recientes, como indica Pablo, relacionadas con la administración pública: Ha acogido el ayuntamiento, la mancomunidad y ahora la comarca. Pero además de estas funciones, ahora, el Molino de Astorito va a recuperar su memoria, ya que parte de sus dependencias se han reconvertido en la Oficina Turística de la localidad y en un museo que recuerda su antaño e importante uso industrial. Una función que fue de tal trascendencia para las localidades de la Canal que como recuerda Pablo Martínez, hicieron que el Molino tuviera hasta su propia canción.

Texto Ainhoa Camino

Pablo Martínez Hermida, a resident of Puente la Reina de Jaca, is one of the few people who remember the details of an infrastructure that was of great importance not only for the village but for much of the Canal de Berdún: the Mill of Astorito or Azorito, a medieval village that gave birth to today's Puente la Reina.

Pablo who, together with his family, runs the bakery of the town (Bakery Apiquera †) was born in 1926 and he says that the mill already existed back then. The origin of the mill is not known. It is known however that in the 18th century, when the old city of Astorito was gone since long, this was the only building that reminded of the medieval village. The construction survived until today, but it has lost its industrial purpose and now hosts the headquarters of the Comarca de La Jacetania in Puente la Reina.

Pablo recalls that the mill was the center of the social life of Puente la Reina and much of the

Canal [de Berdún]. Back then the villages had communal ovens where the women baked

bread from the dough they had prepared at home. But wheat had to be grounded and so

every family went to the mill where news and gossip was exchanged.

The current baker points out that the installation counted two wheels: One was for wheat,

the other for barley. The latter was mainly used as forage for pigs, Pablo Martínez says.

The mill was of the utmost importance for the production of flour. Almost at any time of the year it was used to transform wheat and to make bread. Pablo recalls however that sometimes more than the maximum capacity was requested: The mill could grind about 1 000 kilos a day, but each bag (between 5 and 10 kilos) took about 3 hours, so there were days when people had to wait for much of the day, he says. Pablo also mentions that, as it was a private business, people had to pay for its use. The current baker cannot remember the prices, but he notes that rates were set in terms of the total amount that was ground.

Pablo indicates that in the [19]20s and thanks to a thorough maintenance round and upgrade of the canal, the mill could extend its activities. The mill began to generate electricity, he recalls (*) . Pablo explains that the channel came from the [Río] Aragón Subordán

[weird mental leap here]Although the exact position of the village of Astorito is not known, excavations done in the early 1990s uncovered a cemetery supposedly belonging to it. It was situated in this direction: between the actual roads to Pamplona and Hecho.

Thus the mill became the powerstation of the Canal de Berdún, says Pablo Martínez. It provided light to almost the entire Canal: Bailo, Larués, Santa Engracia, ...‡ There was no comparison with today's light —it was scarcely enough to lit one bulb—, but it was already something. The mill combined both activities —hydroelectric plant and flour mill— until the 1950s. The last owner was a Catalan named Ramón Trullas who, taking his whole family with him, left Puente la Reina in the middle of last century (§). Thereafter the mill fell to the village.

Until now this building played various roles, most recently, Pablo points out, related to public administration: It hosted the town hall, the mancomunidad and now the region. But in addition to these functions the mill of Astorito will now relive its history: some of the outbuildings will welcome the Tourist Office of the town and there will be a museum that commemorates its industrial past that was so important for the villages of the Canal.

In ;

n° 16 invierno-primavera 2008; p 46;

Edita: Asociación Turística

Comarca de la Jacetania, Jaca (Huesca)

*

is a regional magazine published weekly since 1881.

In its issue n°970 of October 27, 1901 a

short notice was published about a survey for chutes and waterfalls suitable for

the production of hydro-electricity.

Nuestro respetable amigo don Juan Trullás, jefe de la casa de su nombre, que en Barcelona se dedica con creciente crédito á la construcción de motores y aparatos de electricidad, se halla recorriendo algunos pueblos de esta montaña, con objeto de reconocer los saltos de agua susceptibles de producir energía eléctrica, para aplicarla con grandes ventajas al alumbrado y otras industrias que puedan implantarse en dichos pueblos.

Less than a month later —in issue n°973 of November 17, 1901— a short report is given and it is clear that Señor Trullas (or is it Trullás?) had spent his time well. He had secured the right to use the water captured at Puente la Reina for 30 years!

De regreso de su exploración por los principales pueblos de nuestra comarca, hallase en esta ciudad de paso para su casa de Barcelona, nuestro respetable amigo D. Juan Trullas, quien ha contratado la installación de luz eléctrica en Ansó, Salvatierra, Berdún y Santaengracia, habiendo adquirido en arriendo por 30 años el potente salto que en el puente de la Reina posee el último de estos pueblos, con cuya fuerza se promete producir energia sobrada para proveer no solo para los compromisos adquiridos sino para otros que está en vias de concertar.

From issue n°1059 of July 12, 1903 we learn that work at the mill and the dam will start very soon.

Muy en breve se dará principio á los trabajos de perfeccionamiento del salto en el llamado Molino de Santaengracia, con objeto de proceder á la inmediata instalación del alumbrado eléctrico en la villa de Berdún.

I would conclude from the above that several villages of the Canal de Berdún were connected to the grid and had the comfort of electricity starting from the first years of the 20th century, several years earlier than mentioned in the interview.

† Pablo Martínez Roldán is a farmer who turned into baker in 1999. The bakery is situated facing the mill just across the road.

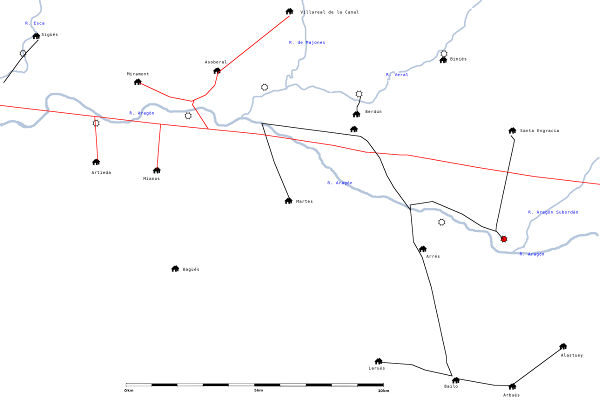

‡ When studying old maps of the Instituto Geográfico Nacional — we need the numbers 175 & 176 — it soon becomes clear that there was some dynamic in the layout of the grid.

Before the civil war

Figure (7) gives the situation based on the map editions of 1932 (left part) and 1934 (right half).

The sketch shows two different networks.

The red line running from left to right is the high-voltage line of the company

Hidroeléctrica Ibérica

running from Lafortunada on the Río Cinca to the energy hungry city of Bilbao.

However, the maps show that five villages (Artieda, Mianos, Miramont, Asoberal and Villareal de la Canal)

received electricity from this line.

That is rather unusual and —though I did check the maps between Lafortunada and Pamplona—

I couldn't find any other village in the same situation.

The local power distribution lines are drawn in black. The molino de Azoguillo (filled with red) feeds eight villages with three main branches. First there is Santa Engracia on its own. Then we have the lower part of Berdún, together with Martes after a large detour. The third branch runs via Arrés towards Larués, Bailo, Arbués and finally Alastuey. Berdún proper, the part on the hill, receives power from it's own mill on the Río Veral.

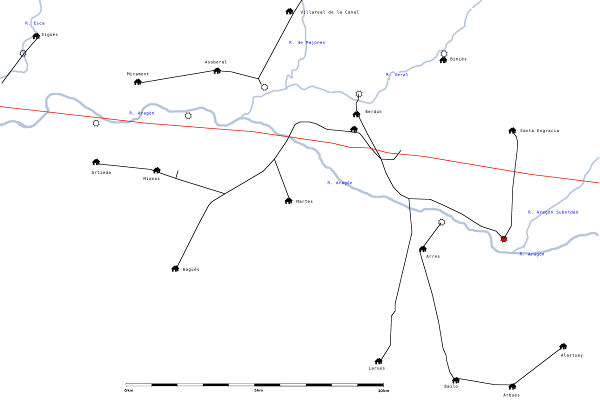

After the civil war

The layout was changed dramatically in the next edition of the maps in 1952. All the connections to

the high-tension line have disappeared and the villages are serviced by several local mills.

Maybe that is because Hidroeléctrica Ibérica had to deal with serious problems. Firstly

in its management but not less important with Lafortunada which was at the other side

of the frontline. Lafortunada was in republican hands and therefore for a couple of years did not supply electricity

to this side of the line.

Arrés is now off the grid and is supplied by its own mill with lines towards Bailo, Arbués and Alastuey. Larués however is on a new branch coming straigth from the mill of Puente la Reina.

More to the West the line is extended beyond Martes. Mianos, Artieda (formerly on the Ibérica line) and Bagüés are also customers of our mill. There is also short branch reaching towards Berdún. The village on the hill counts now with two sources of electricity: its own mill on the Río Veral and the molino de Azorito on the Río Aragón Subordán.

§ In issue n°3954 of July 11, 1959 an obituary is published:

Rogad a Dios en caridad por el alma deand at the bottom of the same page:

D. Ramón Trullás Axcerías

Industrial

falleció en Puente la Reina (Santa Engracia) el 7 de los corrientes

a los 80 años de edad, ....

Ha entregado también su alma a Dios, tras una rápida implacable dolencia, el respetable y muy acreditado y querido industrial, residente hace muchos años en Puente la Reina (Santa Engracia) D. Ramón Trullás Axcerías, de general estimación en esta comarca, ...I presume this is about the same person. This Ramón here had a brother Antonio (1) who was also active in the electricity business, but I couldn't find any indication of the relationship between our Ramón and the Juan mentioned earlier on this page.

(1) — 2002 — La última generación de molinos pirenaicos (Salvatierra de Esca); Cuadernos de etnología y etnografía de Navarra, n°75, p55-107.